Santa Barbara’s rent stabilization push raises hard questions about cost, mobility, and long-term outcomes.

Tuesday night’s Santa Barbara City Council vote was framed as compassion. But compassion without outcomes is not a solution—it is a sentiment. By a 4–3 vote, the Council chose to move forward with a rent stabilization framework that expands regulation, enforcement, and permanent administrative control over housing, while leaving unanswered the most important question of all: how does this help people get ahead?

That question was never meaningfully addressed.

What Tuesday Night’s Vote Did—and Did Not—Do

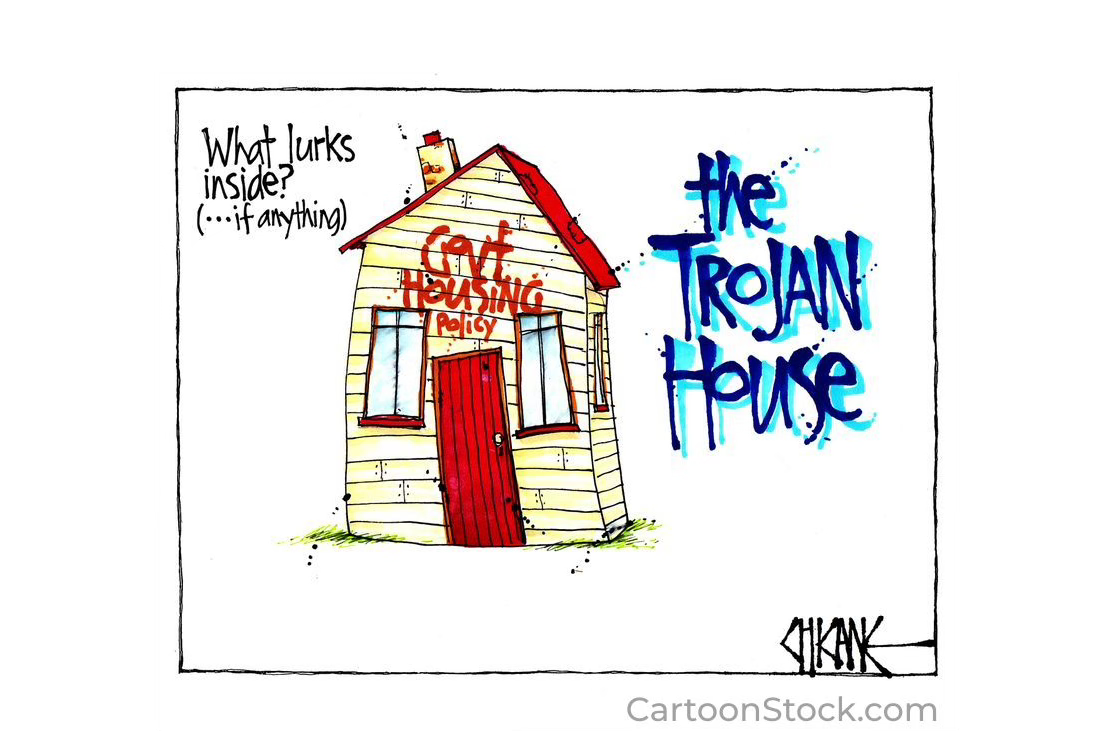

Clarity matters. Tuesday night’s vote did not adopt rent control or set a rent cap. Instead, the Council directed staff to begin designing a rent stabilization program—complete with enforcement structures, administrative systems, and possible interim measures such as a rent increase moratorium. That direction commits staff time, legal resources, and city capacity before any final policy is voted on. Once that machinery is built, the pressure to justify and expand it only increases. This is how cities drift into large, permanent programs without ever having a full public debate about cost, effectiveness, or exit strategies.

The Story That Revealed the Divide

One of the most revealing moments came when Council member Kristen Sneddon shared a personal story about growing up in subsidized housing and pointed to the fact that the property is now reportedly valued at roughly $4 million, presenting that appreciation as evidence the model “worked.”

But the success of that story was never about the building.

A property’s valuation is not liquid funding; it only becomes money if the owner sells the asset. Paper appreciation does not explain operating costs, long-term maintenance, or scalability. It does not fund enforcement staff, hearing boards, or administrative systems.

What actually “worked” was upward mobility.

A child grew up in subsidized housing, received an education, built a career, and no longer relied on public assistance. That is the outcome housing policy should be measured against—not the size, permanence, or market value of the system itself.

Today, Council member Kristen Sneddon and her husband earn a combined income in the range of hundreds of thousands of dollars annually through public-sector employment. That trajectory—education, opportunity, self-sufficiency—is the real success story. It is the model worth replicating.

But the framework the Council majority voted to advance does not focus on how people leave regulated or subsidized housing. It focuses on how to expand and manage it indefinitely.

That is not a hand up. It is a holding pattern.

Permanence Is Not Progress

Expanding rent caps, rental registries, enforcement boards, and long-term controls does not create ladders out of dependency. It creates permanence. Systems grow. Bureaucracies entrench. Housing becomes a destination rather than a bridge.

A system focused on regulation measures success by how many units it controls.

A system focused on mobility measures success by how many people no longer need it.

The uncomfortable question the four council members did not answer is simple:

Where is the off-ramp?

A policy that does not plan for people to exit it is not breaking cycles of poverty—it is institutionalizing them. Generation after generation remains inside the same system, while the system itself grows larger, more expensive, and harder to unwind.

A policy with no exit plan is not a ladder—it’s a loop.

Why the Ellis Act Kept Coming Up

That question helps explain why the Ellis Act surfaced repeatedly during Tuesday night’s discussion, raised by CAUSE and referenced by Council members Meagan Harmon, Kristen Sneddon, and Wendy Santamaria. The Ellis Act is a California state law, adopted in 1985, that allows a property owner to withdraw a rental property from the rental market entirely if they choose to exit the rental business. Even in cities with strict rent control or rent stabilization, local governments cannot force an owner to continue renting once the Ellis Act is invoked. Cities may regulate notice and relocation assistance, but they cannot block the withdrawal itself.

That legal reality matters. When cities layer rent caps, registries, enforcement boards, penalties, and moratoria onto rental housing, the Ellis Act becomes the pressure-release valve. Owners who conclude that operating under increasingly complex and restrictive rules is no longer viable are legally entitled to leave the rental market altogether. The predictable result is fewer rental units, not more.

This is not a loophole. It is state law. And it means local policy choices directly influence whether owners remain in the rental market or exit it. A framework built around permanence and control—without realistic paths for success—risks accelerating withdrawals, shrinking supply, and intensifying competition for the units that remain.

When regulation becomes permanent and inflexible, the Ellis Act becomes the exit.

The Fiscal Reality That Was Ignored

That concern becomes even more serious when paired with Santa Barbara’s financial reality. The City is already operating in a deficit—one that staff has warned is growing. Yet those warnings appeared to carry little weight with the Council majority.

Council members Eric Friedman, Mike Jordan, and Mayor Randy Rowse each raised the same concern on the record: Santa Barbara does not currently have the funding capacity to create, staff, and operate a full rent-stabilization enforcement system.

During the discussion, it was noted that Santa Monica’s rent control program costs more than $6 million annually to operate, cited as a cautionary comparison. If Santa Barbara follows that path, rent stabilization would quickly become one of the largest and most expensive administrative functions the City has ever taken on—at the same time residents are being warned about budget shortfalls, deferred maintenance, and service constraints.

Who Pays When the City Can’t?

When cities create expensive regulatory systems without dedicated funding, the costs do not disappear. They are absorbed through higher taxes, higher fees, reduced services, or deferred maintenance elsewhere.

In other words, even residents who never benefit from the program pay for

it—either directly or through diminished city services. That reality deserves to be part of the conversation before Santa Barbara commits to building one of the largest bureaucratic systems in its history.

The Question the Council Still Owes the Public

Before Santa Barbara builds another permanent system, the Council owes residents clear answers:

What does success look like?

How much will this cost annually to operate?

How many people are expected to move out of regulated or subsidized housing—and on what timeline?

Without those answers, this is not policy—it is hope wrapped in bureaucracy.

Compassion is not measured by how long government programs last. It is measured by whether people no longer need them.

A system that offers only permanence is not a solution—it is a trap. And Tuesday night’s vote moved Santa Barbara closer to building a system that manages dependency rather than ending it.

Real compassion builds exits. Tuesday night’s vote did not.

Blame Isn’t a Housing Strategy

Why California’s affordability crisis can’t be solved by scapegoating

I don’t believe the Council majority is focused on how to help low-income families become higher-income families. Instead, the debate increasingly frames housing costs as the product of “greedy landlords,” as though individual behavior explains a crisis that exists across the entire state. California has the highest housing costs in the nation. That reality points less to widespread misconduct and more to systemic policy failure. If the goal is lasting affordability, the answer lies in expanding opportunity and mobility — not in assigning blame or imposing punishment that ultimately limits choices for everyone.

Opportunity means making it possible for builders to build homes that even lower-income people can afford. As long as California continues an essentially “infill only” policy for new housing, true entry-level housing is impossible.

Opportunity, not punishment, is what ultimately makes housing affordable — because dignity requires independence.

Standard Operating Procedure for our SB govt: the upward mobility that matters most is their own salaries.

B, another well researched and important piece! The problem is that no one is listening to your facts, Peter Rupert's facts or the opinion of every world class economist / pricing dynamics expert re: Rent Control. In fact, last weekend the Wall Street Journal (not something that most of the city council likely reads) had a great article: What the Twin Cities Tell Us About Fixing the Housing Crisis. The sub-headline said it all--St. Paul enacted rent controls, and housing construction plummeted. Next-door Minneapolis generated a downtown boom without regulating rent! Who are these people--some who pretend to be academics--that simply impose their limited world view on our once great city? The arrogance/hubris is unfathomable but, hey, they were elected so perhaps our electorate needs to look in the mirror rather than pointing fingers. Keep up the heat: )))!