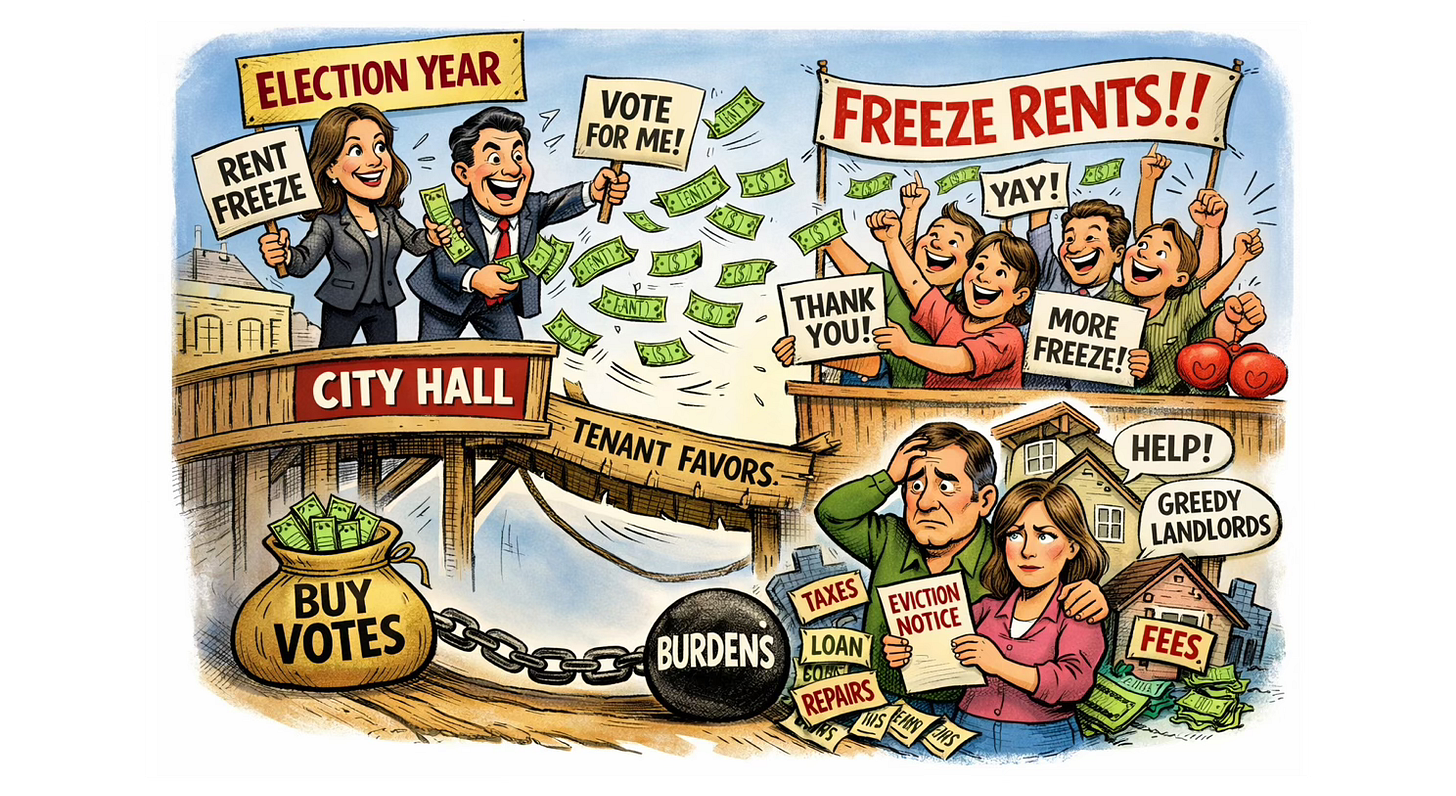

History is unambiguous: rent control has never increased housing supply. It has never lowered rents citywide. And Santa Barbara government policies made supply nearly impossible long before the rent freeze ever appeared.

The city did not experience a population surge. Census data show that Santa Barbara’s population has been flat to slightly declining fo…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Santa Barbara Current to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.