As Santa Barbara City Council prepares to vote tonight on a rent freeze, rent stabilization, and a mandatory rent registry, the public discussion has focused almost entirely on rents. What has received far less attention is the City’s own long-standing policy on cost recovery — and how sharply it conflicts with the framework now being proposed for housing.

On Monday, I received the City’s response to a Public Records Act Request (PRAR) seeking ten years of City-imposed fee and utility increases. Because City Council is scheduled to vote tonight (Tuesday), this column focuses on one illustrative year from that response to show how the City applies cost recovery to itself. A follow-up column will present the full ten-year analysis in detail.

Given the timing of tonight’s vote, it was important to put this information before the public — and City Council — now.

Under the proposal before Council, allowable rent increases would be capped at 60 percent of CPI, even as inflation, insurance, utilities, and City-imposed fees, continue to rise. The premise is simple: housing providers should absorb a substantial portion of rising costs in the name of affordability.

That premise is difficult to reconcile with how the City of Santa Barbara manages its own finances.

What the City Says — in its Own Words

Over the past decade, the City has repeatedly adopted and reaffirmed a clear policy position: when municipal costs rise, fees and rates must rise as well.

City resolutions state that fees exist to “defray the cost of providing programs and services” and that funds needed to cover rising expenses “can and should be obtained by setting fees and charges.” Inflation and CPI are explicitly cited as valid justifications for these increases, and in some cases fee schedules are indexed to CPI automatically.

There is no language in these policies about partial recovery. There is no suggestion that the City should absorb rising costs as a public good. There is no cap limiting recovery to a fraction of inflation.

In the City’s own energy program, Santa Barbara Clean Energy, the principle is even more explicit: rates must achieve “revenue sufficiency,” meaning they are designed to recover all program expenses, debt service, and reserves.

In short, when City Hall’s costs rise, full cost recovery is treated as essential.

What Residents Have Experienced

Residents do not need to read resolutions to understand how this policy works in practice. They experience it every month.

Trash and recycling charges rise.

Water rates rise.

Sewer and wastewater fees rise.

Energy charges rise.

These increases are often annual, frequently compounded, and routinely justified by inflation, labor costs, pension obligations, and operating expenses. They are not capped at 60 percent of CPI. They are not partially absorbed. They are passed through because the City considers doing otherwise fiscally irresponsible.

One Year Makes the Contradiction Unmistakable

The City’s PRAR response documents ten years of fee and utility increases imposed on residents. Because City Council is voting tonight, this column highlights one year from that record.

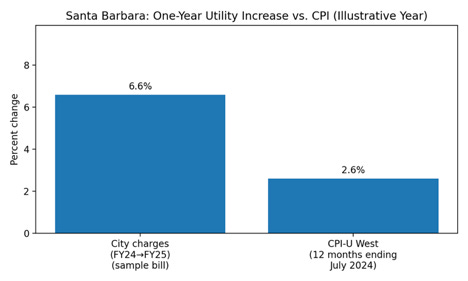

From FY24 to FY25, a representative set of City-imposed utility charges increased 6.6 percent, compared with 2.6 percent CPI-U West over the same period.

Chart: One-Year City Utility Increases vs. CPI (Illustrative Year)

City Utility Increases vs. CPI – FY24 to FY25

Chart notes:

Based on a representative monthly bill (trash base + one 35-gallon cart, water at 4 HCF, wastewater at the single-family cap of 8 HCF).

Not included: voter-approved tax increases — the 1% sales tax under Measure C and the ½-cent sales tax under Measure I — which further increased the cost of living but are separate from utility rates and fee schedules.

A follow-up column will examine all ten years of City increases.

If the City had applied the same 60-percent-of-CPI standard it now proposes for housing providers, these increases would not have been permitted.

The Rent Proposal

Against this backdrop, the City is now proposing a fundamentally different standard for housing.

Under the rent stabilization framework, housing providers would be limited to recovering only 60 percent of CPI, even as many of their largest expenses rise faster than inflation. Insurance premiums, in particular, have surged well beyond CPI in recent years. Maintenance, construction labor, and compliance costs, have done the same.

Layered on top of that are the City’s own rising fees and utility charges — costs landlords pay in the same way residents do.

The proposal does not dispute that these costs are real. It simply requires that a substantial portion of them be absorbed.

A Basic Question the City Must Answer Tonight

Before voting, City Council should answer a straightforward but critical question:

Is the 60-percent cap based on national CPI, or California regional CPI — the same CPI the City relies on when raising fees and utility rates on residents?

This distinction matters. California regional CPI measures have often exceeded national inflation, particularly for energy, utilities, and housing-related costs. The City has relied on these higher regional CPI figures when justifying its own increases.

If the City is using regional CPI to justify full cost recovery for itself but limiting housing providers to only 60 percent of that same CPI, the inconsistency is even more pronounced.

A Final Challenge to Council

This debate is often framed as a moral choice between affordability and profit. But the question before Council tonight is not whether affordability matters.

It does.

The question is whether a policy that selectively denies cost recovery is economically sustainable — or fair.

If limiting cost recovery to 60 percent of inflation is sound public policy, why has the City never applied that standard to its own fees, rates, and utilities?

Tonight’s vote is not just about rent control. It is about whether City Council applies one economic rule to itself — and a different one to everyone else.

•••

Note: This column highlights one year from a ten-year Public Records Act response received Monday to inform the public ahead of tonight’s City Council vote. A follow-up column will present the full ten-year analysis, including cumulative City-imposed increases, CPI comparisons, and the compounded impact on Santa Barbara residents.

Click here to support Bob Smith!

Community Calendar:

Got a Santa Barbara event for our community calendar? Fenkner@sbcurrent.com

This is a great article that shows Bonnie has a clear understanding of this somewhat complicated isolated situation.

My bottom line:

This article is not framed as landlords vs. tenants or profit vs. morality

The central question is fairness and sustainability

If limiting cost recovery to 60% of inflation is good policy:

Why has the City never applied it to itself?

In other words double standard or "do as i say, not as I do."

My takeaway:

Why would a small time (mom and pop) investor ever enter a marketplace like Santa Barbara to build a portfolio of rental properties? It is a zero sum game with no upside.

I think if they vote for a rent rollback to December 2025 and a one year freeze, there should also the same roll back applied to all COLA for city employees, especially the city administrator who was granted a 3.5% increase just a month or two ago.