In the debate over rent regulation, Santa Barbara officials often focus on landlords as the driver of rising housing costs. What receives far less attention is the City’s own role in steadily increasing the fixed, unavoidable costs, of operating rental housing.

The data cited here is not anecdotal. It comes directly from a Public Records Act Request (PRAR) I submitted to the City of Santa Barbara seeking documentation of all City-approved increases over the past ten years. The records produced include water, sewer, trash, and electricity-related charges approved by City Council and passed through to ratepayers. Taken together, they provide a clear, City-sourced record of how essential housing costs have risen—year after year—without any CPI cap.

Water: Increases That Far Exceed Proposed Rent Cap

Between 2015 and 2025, the City of Santa Barbara significantly raised water charges. City records show the water usage rate for the first tier increased 44.29 percent over that period. Even more striking, the mandatory monthly water service charge—paid regardless of use—increased 70.33 percent.

Over the same decade, California CPI rose 41.97 percent. Under the rent-stabilization framework now being discussed locally—60 percent of CPI—allowable increases would have totaled only 25.18 percent.

Put simply, the City raised its own water charges nearly three times faster than the increases it now proposes to allow landlords.

Even in a single recent year, the disparity is clear. From FY 2024 to FY 2025, City utility charges rose roughly 6.6 percent, while CPI-U West increased only 2.6 percent. These increases were approved automatically, without any CPI cap or affordability analysis.

Sewer: A Quiet Doubling Over Ten Years

Sewer rates reveal an even more striking pattern.

In just one year—FY 2024 to FY 2025—the City approved a 9.5 percent increase to both the fixed sewer charge per dwelling unit and the volumetric sewer rate. That increase was not an outlier. It was the continuation of a decade of compounding increases.

Over roughly the past ten years, Santa Barbara’s sewer charges have effectively doubled. The fixed monthly sewer charge per dwelling unit rose from approximately $18–$19 per month to nearly $39, an increase of more than 100 percent. At the same time, the volumetric sewer rate climbed from roughly $3.20–$3.40 per HCF to about $5.95, an increase of 80 to 90 percent.

For a small four-unit property with one meter, this translates into a 95 to 105 percent increase in the total sewer bill for the same level of service.

A sewer bill that once ran about $135–$145 per month now costs $270–$285 per month, without any increase in usage.

These increases were approved year after year, passed directly to ratepayers, and never tied to CPI. If the City had limited its own sewer increases to 60 percent of CPI, as now proposed for landlords, much of this doubling would never have occurred.

Trash: Automatically Passed Through

Trash and recycling follow the same logic. For a small four-unit property using a 1.5-yard dumpster with weekly pickup, City-approved trash rates have increased by approximately 71 percent since FY 2017–18.

Trash and recycling are bundled under the City’s franchise system. When rates rise, they are passed through automatically—no CPI test, no affordability analysis, and no discussion about whether the service provider should absorb the cost.

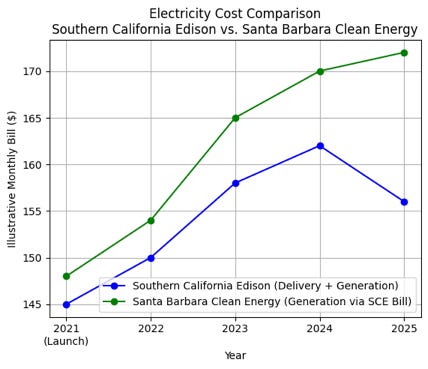

Electricity: A Cost the City Doesn’t Bill—but Still Controls

While the City does not issue the electric bill, it launched Santa Barbara Clean Energy (SBCE) in late 2021, replacing Southern California Edison’s generation charge with City-selected power procurement. Edison continues to bill for delivery; SBCE replaces only the generation portion on the same Edison bill.

SBCE does not add a separate City utility bill or surcharge on top of Edison delivery charges. However, depending on the year and plan, SBCE generation rates have often been higher than Edison’s default supply, particularly for higher renewable options.

SBCE has not existed long enough to produce a ten-year history such as water, sewer, and trash. But since launch, the pattern is clear: electricity costs have changed and risen outside the landlord’s control, just like other essential utilities.

When Utilities Are Legally Defined as “Rent”

In Santa Barbara’s rent-stabilization materials and draft ordinance language, “rent” is defined broadly to include not only the base payment for occupancy but also housing services. Those housing services are explicitly defined to include water, sewer, refuse removal, electricity, utilities, and utility infrastructure, along with items such as parking, furniture, and other services provided in connection with the tenancy.

The City’s materials go further. They state that reducing housing services—or requiring a tenant to begin paying for utilities directly—is treated as a rent increase unless the base rent is reduced to offset the cost.

In other words, a landlord cannot shift rising utility costs out of bundled rent arrangements without triggering a rent violation.

This matters because many multi-unit properties—especially older buildings with one meter—include water, sewer, trash, and sometimes electricity in rent by necessity, not by choice. Under the City’s own framework, those utilities are legally considered part of rent.

The Policy Conflict

Santa Barbara raises water, sewer, trash, and electricity costs through repeated, uncapped increases. At the same time, the City is moving toward policies that would cap rent increases far below those same cost increases, while legally defining the utilities themselves as part of regulated rent.

State law already caps rent increases regardless of why costs rise. Local draft ordinances go further, restricting a landlord’s ability to recover utility costs even as those costs continue to climb.

The result is a one-way ratchet:

City-imposed costs rise freely, while the ability to recover them is constrained—by the City’s own definitions.

Why This Matters

Housing does not operate in a vacuum. Water, sewer, trash, and electricity are essential services. They are controlled or approved by government entities and increased year after year without CPI caps.

If CPI is the standard for fairness, it must apply in both directions.

Because when essential costs double—and rent recovery is capped—the outcome is not affordability. It is deferred maintenance, disinvestment, and fewer housing providers willing or able to remain in the system.

That reality deserves to be part of the conversation.

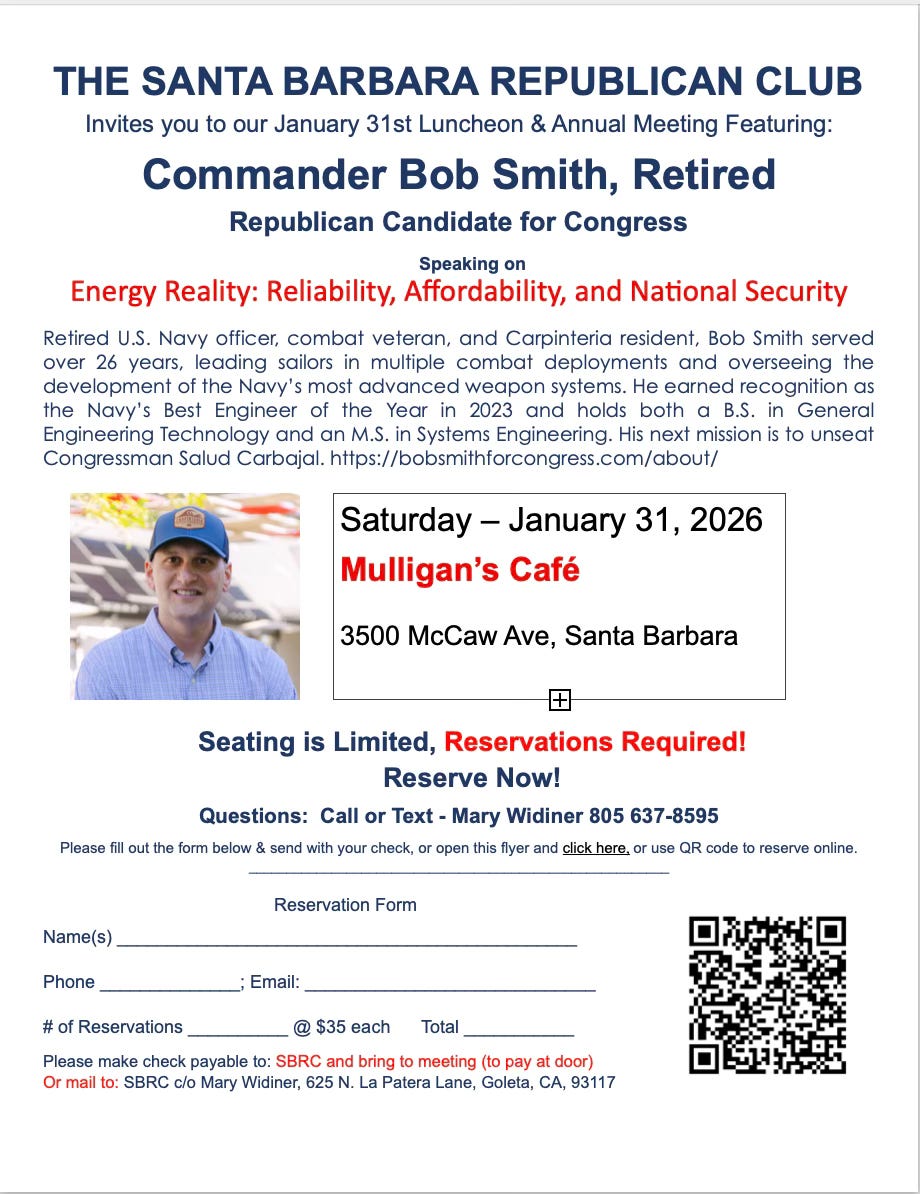

Coming Up Next In (CA-24)

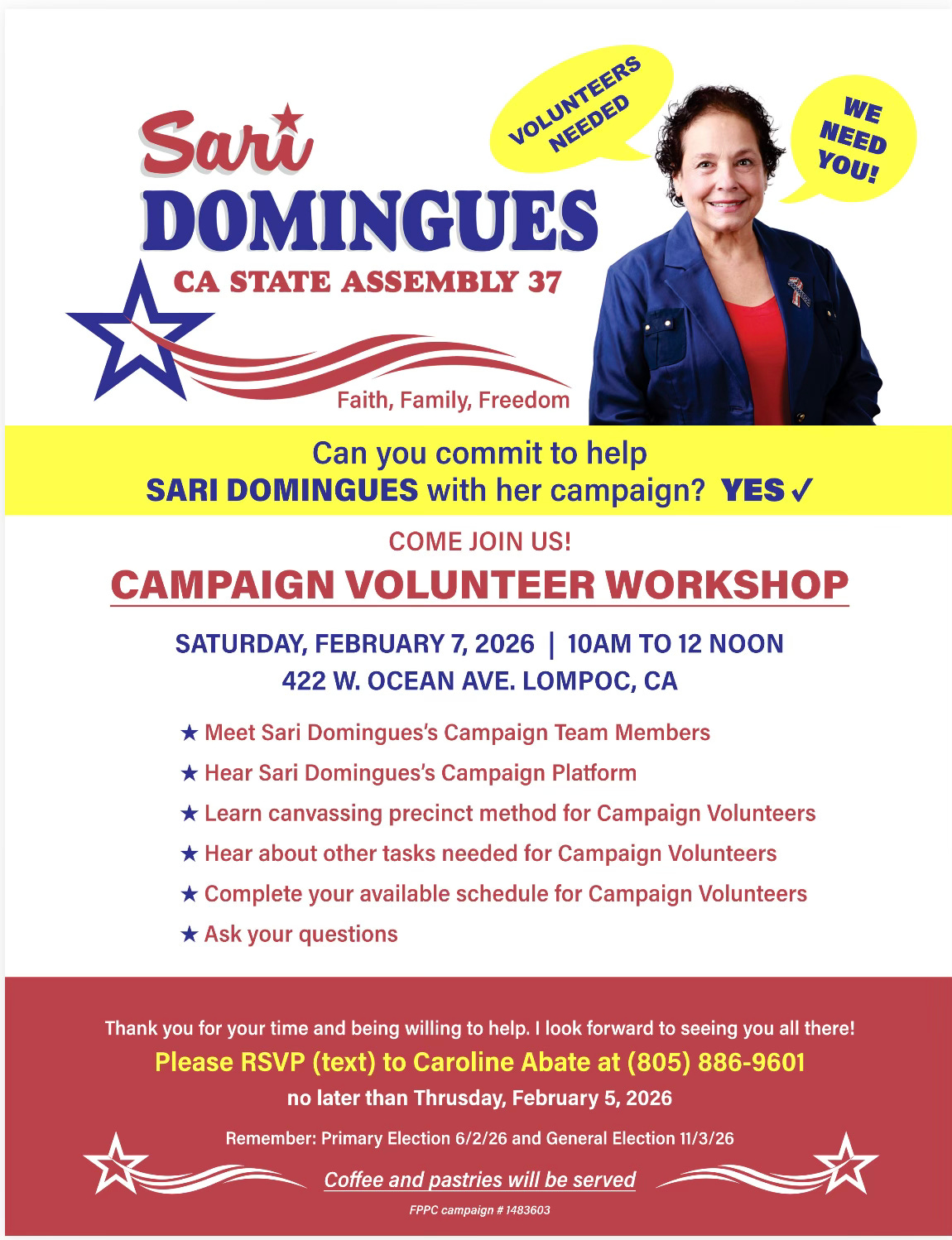

After a pause to let this data sink in, we’ll turn our attention to the congressional race in California’s 24th District.

A new candidate has stepped forward in CA-24

He is not a career politician

His campaign centers on accountability, cost-of-living pressures, and government spending.

Rising energy costs, utility bills, and affordability are part of the conversation.

Voters will have a chance to hear who he is, where he comes from, and why he’s running.

More on that next week.

•••

Meanwhile…

In the latest installment of the Hannah-Beth and Dale Show on KEYT, former State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson and former Santa Barbara City Councilman Dale Francisco were invited to discuss two topics in the news: The U.S. removal of Nicolas Maduro as self-appointed leader of Venezuela, and the continuing ICE operations in Minneapolis.

The first video is the segment on Venezuela. If you click on the little gray arrow symbol in the middle right on the video frame, it will take you to the second video, the ICE discussion.

Community Calendar:

Got a Santa Barbara event for our community calendar? Fenkner@sbcurrent.com

Bonnie, wonderful reporting!! Have you considered posting/publishing to a wider audience? The data and the manner in which you present them is so compelling that I think all but the extreme would see and agree with you.

Good job Bonnie, too bad you don’t run for council!🌸