There’s a strange, almost invisible trade-off that has unfolded over the past twenty years, and most young adults never realized they were participating in it. Many people talk about the housing crisis: too little supply, high demand, zoning that borders on impossible, and prices in places like Santa Barbara that feel more like fantasy than economics. Add inflation, stagnant building policies, and regulatory delays that drag out even the simplest projects, and it’s no surprise that costs have spiraled upward while the homes themselves haven’t become meaningfully “better.”

They simply kept pace with a shrinking dollar.

But under all the charts and policy debates sits a quieter shift—one that’s harder to admit out loud. And that is that the first major financial commitment for Millennials and Gen Z wasn’t a home.

It was school.

For older generations, the early twenties were the years you scraped together a down payment, bought a starter home (or at least had a shot at one), and planted your roots. For today’s young adults, that first major purchase morphed into a degree.

Or two.

Or three.

The turning point wasn’t cultural or emotional; it was structural. Once the federal government guaranteed student loans, universities responded exactly as anyone who studies economics would expect. If the money is guaranteed, and you’re not on the hook for it, raise the price. If the borrower can’t default, raise it again. Tuition didn’t skyrocket because education suddenly became more valuable; it skyrocketed because federal policy made unlimited and consequence-free lending possible.

Universities adapted accordingly. What were once lean educational institutions slowly transformed into sprawling bureaucratic ecosystems: layers of administrators, coordinators, specialty offices, marketing departments, student-life divisions, consultants, and committees for every new concern. Each layer came with a cost, and those costs were passed directly to students who had been told that debt—no matter how large—was simply the price of admission to a stable future.

It’s now common for a graduate or doctoral program to leave students carrying $150,000–$200,000 in principal before interest begins compounding into something far harder to track, plan for, or escape.

That’s a mortgage payment without the house.

Meanwhile, housing affordability collapsed under its own policy pressures. Zoning restrictions choked supply. Regulatory timelines slowed new construction to a crawl. Environmental and compliance requirements layered cost and uncertainty onto every project. And as national fiscal policy devalued the currency, asset prices rose in ways that had nothing to do with local value or quality of life.

So, the same generation that took on mortgage-sized student debt entered a housing market where real estate had become increasingly scarce, increasingly inflated, and increasingly unattainable—especially in coastal cities like Santa Barbara, where entry-level housing stock barely exists.

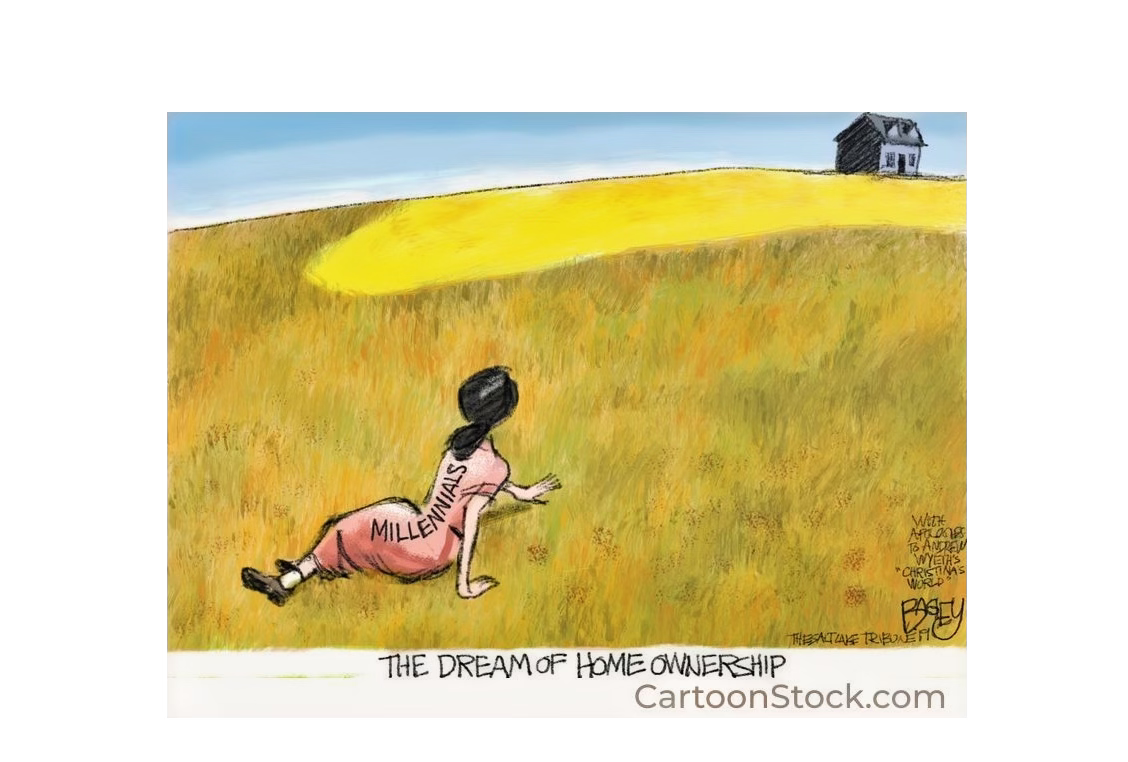

Here’s the part most people miss: Millennials and Gen Z didn’t become “anti-homeownership” by taste, temperament, or lifestyle. They became the never-home generation because the financial breathing room required for homeownership was already consumed before they ever earned their first real paycheck.

Their down payment went to tuition.

Their early financial runway went to interest.

Their first big “investment” wasn’t an asset at all, but a credential whose price had been inflated by the system built to deliver it.

And once you see that, it becomes obvious that young people weren’t the ones who failed; it was Government that failed. The twisted truth is, they did buy a home—just not the kind with a roof and a foundation. They purchased a credential instead of an appreciating asset, and the debt attached to it grows faster than wages, faster than inflation, and faster than any reasonable person can plan around.

This has created an odd moral narrative in our culture. Older generations often ask why young people aren’t building wealth the way their parents did. Younger people wonder why the math seems upside-down no matter how disciplined they are. Both sides are looking at the same picture, but from different vantage points: one sees a failure of budgeting, the other sees a system that completely rearranged the order of life’s major financial steps.

The tragedy isn’t that young people aren’t buying homes. It’s that the system pushed them to buy a different kind of home first—a financial structure with no walls, no equity, and no resale value—and no one ever told them that the choice was irreversible.

That’s the real story: a generation didn’t lose interest in the race towards homeownership.

It lost the ability to get to the starting line.

Community Calendar:

Got a Santa Barbara event for our community calendar? Fenkner@sbcurrent.com

Excellent article. I noticed this ten years ago when I learned that many of my nieces friends were attending the same college she was. I knew they were not star students and from families not poor enough to receive Pell grants but not wealthy enough to afford tuition. My niece explained they were able to get these hugh loans without the consent of their parents. It seems liked a bad idea to me at the time. And turns out it was.

But the good news is they’re all impeccably educated in CRT.