When Cost Recovery Applies to City Hall but Not to Housing Providers

As Santa Barbara considers new rental regulations, the City’s own budget documents highlight a central issue of fairness: When the city faces rising costs, those cost increases justify increasing taxes and fees by the same amount. But when people in the rental housing business face increasing costs–some of those costs imposed by the city–they are told they can only recover a portion of the costs of doing business. This amounts to a forced charitable contribution by landlords to tenants. Which may be good politics in an election year–there are more tenants than landlords–but in the long run it will cause landlords to exit the rental business, further reducing the stock of rental housing.

As Santa Barbara’s housing debate intensifies, it increasingly rests on a simple assertion: landlords have “no right” to consider their costs when setting rents. We are told rents are determined solely by market conditions, and that rising expenses — even those imposed by the government — must be absorbed.

That assertion becomes difficult to reconcile with how the City of Santa Barbara manages its own finances.

When City costs increase, fees, taxes, and rates are adjusted accordingly. Water, sewer, and trash rates rise. Business license fees and service charges are recalibrated. These changes are routinely justified as necessary to sustain services and maintain fiscal stability.

At the same time, property owners who pay these costs are told that cost recovery has no relevance to rent. This tension now sits at the center of the City’s discussion around a rental registry and expanded rent regulation.

The issue is not philosophical. It is whether the City applies the same principles of fairness to its own business and to the businesses of citizens.

The City’s Budget Reality: Cost Recovery as Policy

In late 2025, City staff presented the Finance Committee with a comprehensive set of budget options to address Santa Barbara’s structural deficit. That document — Attachment 5 to the agenda — outlines hundreds of potential revenue and cost-recovery measures.

The list assigns fiscal estimates to specific actions and reflects a clear operating assumption: when costs rise, cost recovery mechanisms must follow.

Among the options identified by staff are:

Increasing engineering service charges to full cost recovery, estimated at $5.4 million annually

Raising the Utility User Tax, projected to generate $3.2 million per year

Expanding paid parking and penalties, totaling more than $2.4 million annually

Expanding Transient Occupancy Tax revenue from short-term rentals, estimated at $2.5 million

Updating planning, building, and environmental review fees to better reflect actual service costs

Complete list here: presentation.xlsx

These examples alone account for more than $20 million annually, and they represent only a portion of the total list. The broader takeaway is clear: cost recovery is not an exception in City policy — it is the norm.

That context matters, particularly as the City considers policies that restrict how housing providers respond to cost increases imposed by those same municipal decisions.

Rental Housing as a Regulated Business

The City already regulates rental housing as a business activity. Property owners are required to hold business licenses, pay business taxes, comply with inspections, and meet ongoing reporting and regulatory requirements.

In most respects, rental housing is treated as a regulated commercial enterprise.

However, when the discussion turns to pricing, the framework changes. Cost considerations that are recognized in other regulated activities are set aside. Landlords are expected to absorb rising expenses indefinitely, even when those expenses stem directly from City-approved rate increases or mandates.

This distinction is particularly significant because many of the largest costs landlords face are not discretionary. Water, sewer, and trash services are City-controlled or City-approved monopolies. Property owners cannot seek alternative providers or renegotiate terms. When rates increase, payment is mandatory.

Yet within the current policy debate, these non-optional costs are treated as immaterial to rent. That’s not how the City evaluates its own fiscal obligations.

Rental Registries and Compliance Costs

Rental registries are often characterized as administrative tools. In practice, they create ongoing compliance obligations: data submission, updates, deadlines, enforcement exposure, and potential penalties. For many owners, compliance requires professional assistance.

These are recurring operational costs that accumulate over time, layered on top of utilities, taxes, insurance, and maintenance. They are real, predictable, and measurable.

Tenant Outcomes in Practice

Rent control and rental registries are commonly presented as beneficial to tenants. However, experience in California cities with long-standing rent regulation provides important warnings.

In Los Angeles, Santa Monica, and Berkeley, rent control has existed for decades. The outcomes are well documented.

First, most renters are excluded. Rent control typically applies only to older housing, leaving a majority of rental units exempt. New renters, younger residents, and working families often receive none of the benefits rent control supposedly provides.

Second, housing mobility declines in a rent-controlled market. Because of their artificially low rents, tenants remain in units longer than they otherwise would, reducing turnover and availability. When units circulate less frequently, options narrow and pressure increases elsewhere in the market.

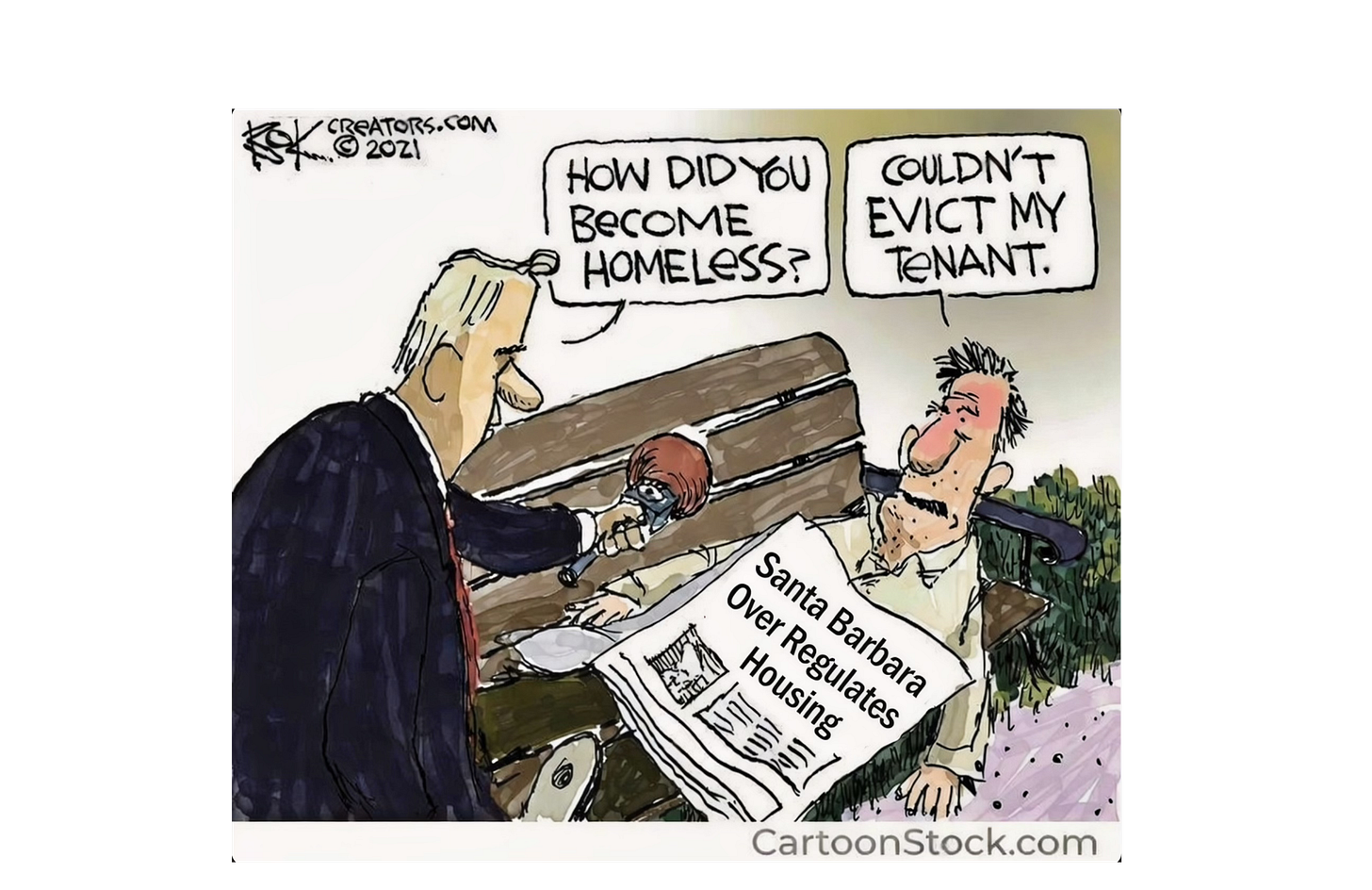

Third, supply and quality are affected. When rent adjustments are constrained but operating costs continue to rise, owners respond by deferring maintenance, postponing improvements, or reducing reinvestment. Some exit the rental market altogether.

These outcomes are not unique to any one city. They reflect consistent responses to sustained cost pressures under similar regulatory conditions.

The 1995 Cutoff and Uneven Application

Rent control in California does not apply to housing built after 1995. This exemption stems from the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, which restricts rent control on new construction and preserves vacancy decontrol.

The intent was to avoid discouraging new housing production. The practical effect has been the creation of a two-tier rental system: older units subject to regulation and newer units fully exempt.

Tenants in newer housing — often younger residents and newcomers — face higher rents and fewer protections. While lawful, this structure results in uneven treatment across the rental population.

Considering Santa Barbara’s Context

Supporters of expanded regulation often argue that Santa Barbara is distinct. The policy tools under discussion, however, are not.

Santa Barbara already faces rising utility rates, increasing regulatory costs, limited housing availability, and a structural budget gap acknowledged by City staff. Introducing additional layers of regulation that will require more expensive city staff for enforcement is just adding to the city’s financial problems, not solving them.

Accountability lies with City Council

It’s important to be clear about accountability. City staff and department administrators implement policy; they do not create it. Every fee increase, rate adjustment, tax proposal, and regulatory expansion discussed here comes from a vote of the City Council. Those decisions have already increased the underlying costs of operating rental housing, contributing to rent increases over time. With several council members now seeking higher office, it is worth noting that these outcomes are not abstract — they are the direct result of how those council members voted. The public can observe those choices being made at the City Council meeting on Tuesday, January 13, 2026, at 2 pm.

Community Calendar:

Got a Santa Barbara event for our community calendar? Fenkner@sbcurrent.com

Excellent summary. Sadly the Liberals that run California got the ‘socialism is the way’ memo. As they are driven by ideology not facts or common sense well stated cases like this will get a lot of nods and smiles from our politicians followed by voting socialist anyway. Ca is going down. People are leaving. It looks more like a third world country now than it did even 5 years ago. The only real solution is to end one party rule that Democrats have ensconced in Blue States. And that will be difficult. Voter ID is thus the solution to this problem. Without illegal alien votes Democrats will lose. Sign the voter ID petition!!

In the early 1980’s I lived in a rent controlled apartment in Santa Monica. In order to get the apartment required applying through a broker of sorts who would charge a $1000 fee to get your application considered. Competition for these cheap apartments was fierce and only applicants with the highest incomes were successful. The apartments were run down and tennants were forbidden from making improvements themselves. I believe the landlords wanted the apartments to be as run down as possible to amplify their case that rent control was turning the neighborhood into a ghetto, which it was. In the end rent control created a black market from which apartment brokers profited. Successful applicants were those with the greatest income so it did not serve the poorest which it was intended to do.